A Good Soak

A French toast experiment

I have been asked quite a few times how long bread should be soaked for French toast. If I’m being honest, I have, at times, been on both sides of the spectrum, and resolved myself to the fact that how long you dip or soak your bread for French toast depends on the type of bread you are using.

Less dense, less chewy breads can take, and in my opinion, require longer soaking periods. Fluffy, light breads require less time.

The thickness of the slice of bread also plays a part. Obviously, the wider the slice, the longer it will need to set in the custard, lest it remains dry in the middle during cooking. There are some general principles to follow, but I think that an experiment is in order to allow for the ability to see what happens when bread is soaked very briefly, not so briefly, and for an extended period of time.

In this circumstance, I’ll do this with three different types of bread: regular-ol’ white bread, a country-style sourdough loaf, and thick-sliced brioche. Although I’m fully aware that brioche that is twice as thick as the other breads in this “experiment” is a bit like comparing apples to oranges, in this situation, I chose the thick slices for practicality purposes. Although you can slice brioche thin, and you can even find pre-sliced loaves occasionally in grocery stores, I contend that those thin slices are not desirable for this application.

Each type of bread will have a slice soaked for 10 seconds, 30 seconds, one full minute, and ten minutes, in the custard from my base French toast recipe, then cooked for three minutes per side at 275 degrees F. I’ll do everything in my very amateur-photographer ability to match the pictures, so that you can best see the differences between each.

Interestingly when I started conceptualized this writing, I asked myself “what happens when you soak French toast for too long?” When I finished the “experiment,” I began to lean more heavily into the concept of “what can we learn when we fail intentionally?”

In private, I have been developing recipes for and writing about breakfast for more than two years. I accumulated enough knowledge of French toast in that time (and my prior 30 years of cooking) to know, for the most part, which of these soaking timeframes were most likely to succeed. What I did not anticipate was how valuable the opportunity to directly compare soaking and cooking different bread types.

Gluten Structure and Bread Density

For one thing, I think I just scratched the surface of understanding just how much a sturdy gluten structure affects how French toast should be soaked and cooked. White bread, for example, has a fairly weak gluten structure. In a perfect world (and the commercial bakeries that make plain white bread come absurdly close to perfecting their recipe and repeating it without flaw or error), white bread is meant to be a soft, reasonably delicate, neutrally flavored bread that you can use for just about anything. Its soft nature makes it an ideal candidate for soaking briefly.

Brioche, on the other hand, has a very weak gluten structure. It is meant to be pillowy-soft, dense but very delicate, light and sweet. Because it is typically sliced thick (particularly in the case of this experiment, where it was twice as thick as the white and sourdough breads), it can hold up to longer soaking period, but its texture changes drastically. Because it is so soft, and its gluten structure so weak, the longer it soaks in custard, the more the center of the bread liquifies as it cooks.

Finally, the sourdough, with its highly developed, stiff gluten structure, and pocketed, almost waxy texture, stood up to every bit of soaking I could throw at it, and still maintained its structure. In my opinion, the sourdough slices I tested were better the longer it soaked; at the ten-minute test, it seemed as though its starchy texture began to break down slightly, which made the cooked French toast lighter and less chewy. That said, this was grocery store sourdough bread, not stuff from an artisan bakery. Down the line, I may test what I bought against a really high quality bread to see what the difference would be, but in my experience, good sourdough is chewy while still remaining soft, and this commercially produced, pre-sliced stuff didn’t quite live up to those traits.

Caramelization

An obvious conclusion to come to is that the longer a piece of bread soaks in custard, the longer it will have to sit on the cooking surface to caramelize. For one thing, much more liquid needs to cook off for the bread to start browning properly, but another important note is that the abundance of inherently colder custard in the bread will lower the surface temperature of your pan or griddle when you lay the slice of bread on it, which will again extend the required amount of time for caramelization.

Another observation is how the sugar content of the bread affected how well it caramelized, particularly with the long soak times. These breads were all soaked in the exact same base French toast custard I released previously, so none received more added sugar than the other. The white bread and brioche, which are both noted as high-sugar breads, still managed to caramelize in the allotted cook time, while the sourdough, which has no added sugar, struggled when soaked longer.

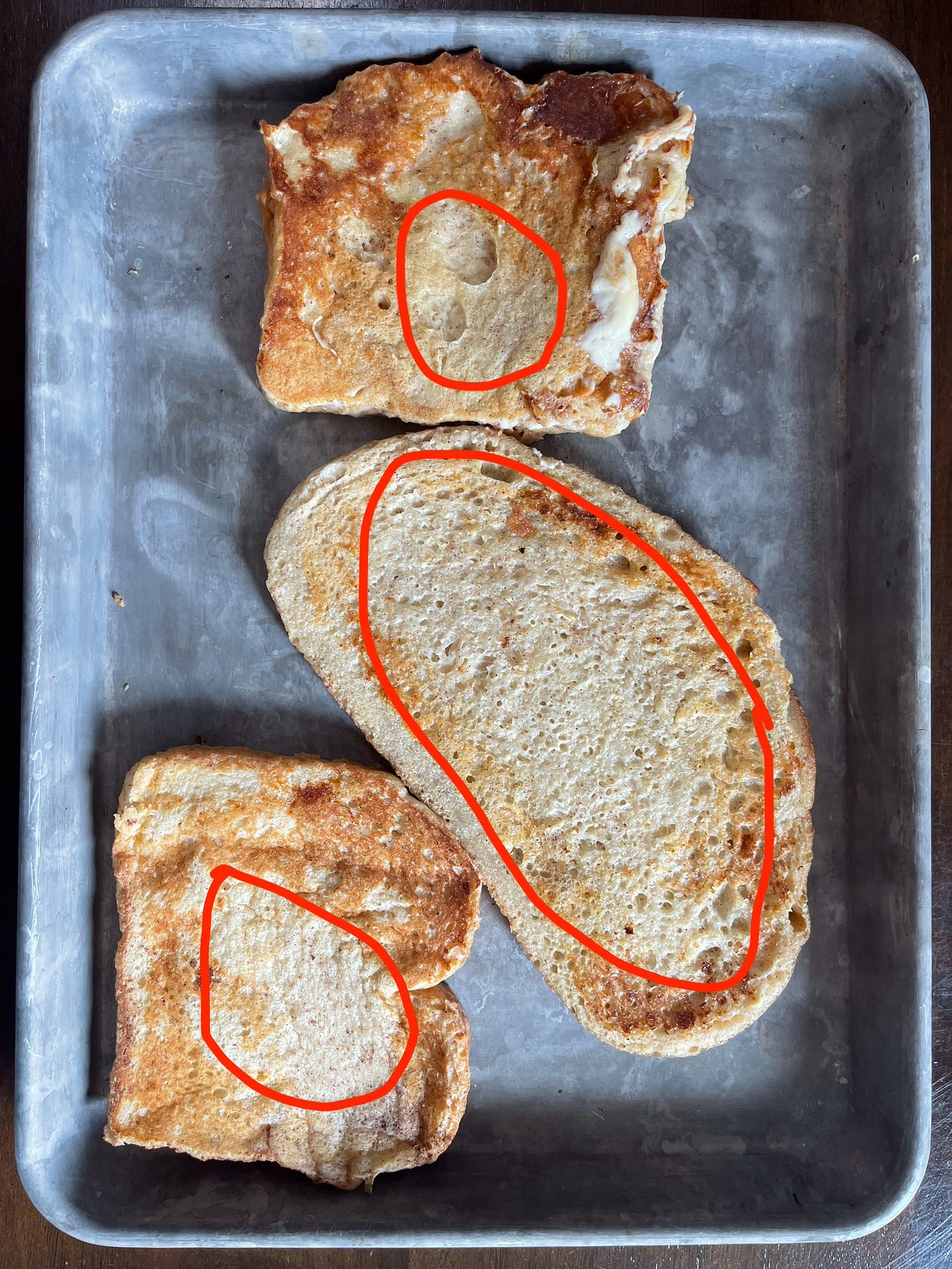

The most surprising observation I had, though, was about an air bubble. As the slices of breads sat for more extended times in the custard, I noted during the process of flipping and removing them from the griddle that they shared a common trait: an either un-or-under-caramelized spot, typically on one side of the bread.

After I finished cooking all the trial slices that were photographed, I set out to cook a few more that sat for a full ten minutes to try to track down this spot. What I noticed was that during the cooking process, the slices of bread would begin to puff-up in the middle. Originally, I had thought that this was the custard in the bread expanding slightly as it cooked, but when I peeked underneath the slice as it cooked, I noted that the puffed-up spot corresponded with the characteristic under-caramelized spot. From what I can tell, the excess of custard in the bread began to seal-off the outside edges against the cooking surface as the French toast cooked, which trapped steam and air that was being released from the cooking process in a pocket, or an air bubble, underneath the bread. This was forcing the slice of bread away from directly contacting the cooking surface, which meant that it didn’t caramelize. The very simple solution to this is to gently lift one corner of the bread with a spatula during cooking, to allow that air to escape (you might think you can push the bubble down lightly with a spatula, but I tried that, and while the air bubble subsided, it seemed to compress the bread slightly, so I don’t recommend it).

Cook Times

This is where the most obvious intentional fail happened for me. Everything inside of me was telling me to cook the breads in batches by their type, with the white bread first, then the sourdough, and finally the brioche. I knew that these different types of bread would ideally need to be cooked at different temperatures and for different amounts of time, largely depending on their times soaking in the custard.

Something I didn’t anticipate, though, was that the sourdough didn’t follow that logic. As I mentioned, it soaked up all the custard I could give it, and that custard set properly, but its problem was that it didn’t caramelize properly in the allotted six minutes. In this case, its cook time had more to do with the thickness of the bread (which was the same thickness as the white bread) and the sturdiness of its gluten structure. From what I can tell, the fix for its caramelization problem was to raise the temperature and cook for the same amount of time.

Unlike the white bread and brioche, which slowly leaned farther towards a texture I can only describe as goo the longer they soaked, the sourdough actually got better. As I mentioned previously, it was only at the point where it was soaked for ten minutes prior to cooking that its starchiness and gluten structure began to really soften, which actually made it better.

Wrapping Up

There are two goals for an experiment like this: develop better cooking instincts and make better French toast. Bearing in mind those things, any lessons learned are worthwhile, but to me the most important thing to take away is this:

Even if your French toast didn’t caramelize to perfection, if you had to cook it for another few minutes on each side, if it was a little dry or slightly too wet, it’s still French toast. If you get the seasonings right, it’ll still taste great, so you shouldn’t ever fear making mistakes, because learning from those mistakes is what will make you a better cook. Or maybe more appropriately, learning from my mistakes will make you a better cook.